Can Authenticity Drive Bottom-Line? This Startup Shows You How

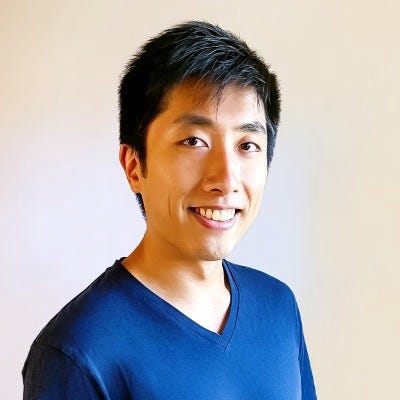

Q&A with Alan Zhao, Co-Founder and CTO at Y-Combinator Startup Warmly,

Originally published on Medium, this story is part of the Entrepreneurship of Life series, a collection of interviews with immigrant startup founders, venture capitalists, and tech business leaders.

Introduction

We talk a lot about founder-market fit for startups, but even so, you don’t often speak to founders for five minutes and get the feeling that, in a way, they are exactly what they build. Alan is one such founder.

With his three partners, Alan Zhao co-founded Warmly, (comma included, as in the sign-off to an email), a platform that helps B2B companies authentically connect with their customers, starting with tracking customer job changes that may trigger relationship maintenance dialogues. In less than a year, Warmly, graduated from Techstars and Y Combinator, raised $2.1 million of seed funding, and had its four co-founders featured in Forbes 30 Under 30.

This is not a team of ordinary humans: Max Greenwald, a Princeton graduate and 50-mile finisher in the 24-hour World’s Toughest Mudder challenge; Carina Boo, a tech guru and chicken farmer in her free time; Val Yermakova, a circus aerialist, ex-competitive wrestler and figure skater, and Fulbright scholar; and Alan, a self-taught engineer, ex-restauranteur, and Wushu (Chinese martial arts) master. Despite their unique backgrounds, the quartet all seem to live and breathe what Warmly, stands for at its core — authenticity and warmth, against a backdrop of business savvy.

Alan recently sat down with me and shared about his Warmly, journey and the nonlinear path that took him from the Wall Street trading floor to Silicon Valley. Among other things, we talked about:

How was Warmly, born in an urgent pivot after the team’s last idea had failed?

If this makes so much sense, why hasn’t someone done it already?

Insider scoop on the legendary YC (Y Combinator) program?

Advice for startups raising a seed round?

How do the four co-founders work together and bond?

Why become an entrepreneur?

Craziest story while running a pho restaurant?

Experience growing up and navigating careers as a Chinese American?

Let’s hear what Alan has to say.

Warmly, Experience & Reflections

How did the four of you come together, and what was the iterative process that led to Warmly,?

My three co-founders — Max, Val, and Carina — met at Google and bonded over their shared interest in starting a company. Max (our CEO) was a product manager, Carina (our CTO) an engineering manager, and Val (our CPO) a designer. [Keyi note: since this interview was conducted, Alan has taken over the CTO role, Carina is serving as CPO, and Val is pursuing a different passion.] Max and I met in late 2019 at On Deck, a fellowship program for would-be tech founders, and we grew close through a Hackathon project where we co-built a Twitch-like gamer streaming platform that allowed spectators to vote real-time on what the streamer’s next move should be.

It was a fun ride, so we decided to team up again — this time with Val and Carina — on PushPull, an authentic digital business card. We created an online community where professionals connect through personal PushPull cards that “push” things they are willing to offer strangers and “pull” asks that anyone could respond to. The idea was inspired in part by Adam Grant’s Give and Take, a favorite title of Max’s. We wanted to bring more authenticity into the business world, where authenticity can be a luxury.

The four of us applied to Techstars with the PushPull idea and got admitted. We started the program in Boulder, CO in January 2020. As we talked to investors, however, critical questions started to emerge: are there enough “givers” to sustain our community? Can we create an effective “throttle” so that someone with a sought-after “give” would not be overwhelmed with a flood of requests? How do we match people with asks to those who might help them? Halfway through the Techstars program, we weren’t growing at a satisfactory clip and didn’t have a conceivable path to monetization. It was a hard decision, but we knew we had to pivot. Time was running out, and we could only afford one week to figure out a new direction.

Influenced by Techstars’ strong B2B DNA, we contemplated turning PushPull into a community for enterprise customers. This drew our attention to the growing customer success function in SaaS companies. We realized the authenticity concept that we built PushPull around has a bigger role to play in customer success versus, say, in sales, and became even more intrigued. As all of us came from a B2C background and were B2B newbies at the time, we set up over a hundred informational calls with anyone working in customer success that we could get on the phone. As we learnt about their job and pain points, five product ideas began to take shape, and tracking customer job changes — what Warmly, does today — was one of them.

For B2B businesses, the job change of a key individual on an existing account represents both a threat and an opportunity. If whoever replaces the job changer prefers a different vendor, the B2B company risks losing the account. On the flip side, if the job changer was a happy customer, the B2B company now has a warm sales lead into his/her new employer. Therefore, knowing about customer job changes real-time could be highly valuable.

As the five product ideas seemed equally relevant for our prospective clients, we had a heated debate about which one to go with. We landed on tracking job changes eventually, because it appeared most straightforward and likely to gain traction by our next milestone merely six weeks away — the Techstars Demo Day.

Since that decision was made, it took us less than a week to land our first sale. We spun up the first iteration of Warmly, and announced it within the Techstars community. Soon we got our first inquiry from a fellow Techstars founder and set up a demo with him. We had not completely figured out our backend at the time and had to “hack” it. We were demonstrating how Warmly, would automatically detect Max’s hypothetical job change when he updated his LinkedIn profile. Our prospective customer said: “Ok, let’s say you just joined the CDC.” As Max was editing his LinkedIn, Carina was putting CDC into our database real-time so that it could capture Max’s “new employer”. We were so nervous that a typo might blow the demo and repeated “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention” again and again to make sure she got every word right — our potential customer probably raised an eyebrow on the other side of the call.

Finally, Max saved his LinkedIn edits and refreshed the Warmly, page while the rest of us held our breath. There he was — right on the job change dashboard!

“Great,” our prospective customer said without hesitation, “how much does this cost, and how do I pay?”

We were stunned in disbelief — what just happened? Did we really just make our first sale? We were in such early innings that neither pricing nor payment logistics had even been discussed. So Max improvised and said: “We charge — uh — $99/month, and we take… credit cards?”

After the call, we tore off a piece of paper, wrote “$99” on it, taped it to the wall and all took a photo underneath, beers in hand. This initial milestone kicked off the momentum: we had locked in 20 or so purchase commitments even before we built out the actual product. The pivot worked.

Why had nobody else before Warmly, successfully done what Warmly, attempts to do? What is the most non-obvious or tricky thing about your business that others failed to either appreciate or solve?

We were lucky to start Warmly, at the right time with a few tailwinds in the industry.

First, the “SaaS-ification” of enterprise tech in recent years has significantly increased churn risk for B2B companies, forcing them to invest in customer success to improve retention. The industry used to focus predominantly on the sales funnel, which was considered “close to the money”. During the on-premise IT era, once a deal was closed and the software or system was deployed across the customer’s servers, the lion’s share of revenue was earned, and the customer would be “locked in” for years. Today, with cloud service delivery, subscription models, and free trials becoming the default, customer churns are easier and more frequent than ever. Therefore, it becomes crucial to detect and mitigate potential churn risk, such as the job change of a key decision maker, as early on as possible.

Meanwhile, the industry is increasingly recognizing new sales opportunities from the existing customer base. Customer relations used to be intentionally walled off from sales (in part to keep the former “authentic”), with no expectations to drive revenue. However, the bright side of churns from job changes is a growing opportunity to sell into a new account through a customer advocate. Account churns are bad, but individual churns can be great. B2B companies are increasingly thinking about what we call LTVC (Lifetime Value of Champions, or customer advocates), and we are here to help them maximize it.

In the meantime, tracking job changes is a much harder technical problem than it may appear. We initially thought building the system would be a weekend project, and we couldn’t be more wrong. I cannot go into specifics here, but the bottom line is there is no universal source of truth. You need to combine and triangulate a variety of information from multiple channels and come up with smart ways to deal with edge cases. You also need to diligently maintain the freshness of your data. All these factors make this problem tricky to solve, but this is exactly why we’re here, because otherwise the problem would have been solved already.

Can you talk about your go-to-market strategy?

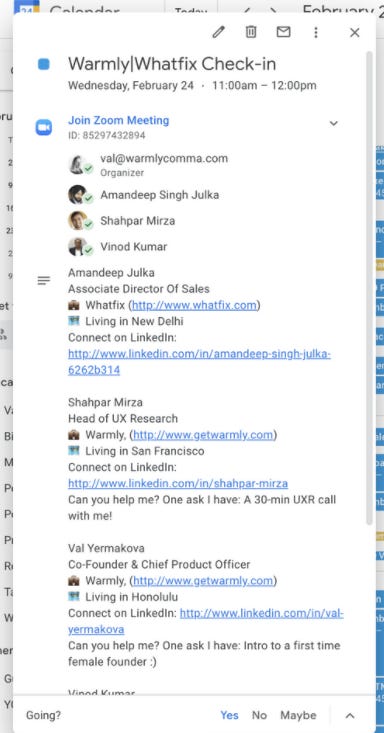

We’ve launched warmly.ai, our newest product that provides instant context on every person in a virtual meeting. We’re taking a two-pronged approach to promote its adoption: a bottoms-up “freemium” model facilitated by our Google calendar integration, and an enterprise-oriented top-down approach through our partnership with an established enterprise SaaS player. (I can’t reveal the name just yet, stay tuned!)

Individual users can grant us access to their Google calendar, and we will automatically enrich their future meeting invites with available profiles for all participants, so that they could head into meetings equipped with more context on who they speak to. Their guests will see the enriched meeting invites as well with an attribution to Warmly, and they can click through the link to sign up in a matter of seconds. This way, our early adopters naturally spread our name among their professional networks.

Meanwhile, our integration into the established SaaS platform was a critical milestone that grants us access to their growing ecosystem and deep pool of enterprise clients. We were lucky to be featured as one of their “Best-of-Breed” apps, alongside well-known SaaS players like Dropbox and Slack. This would not have happened without the relentless effort by Max and our go-to-market team: they were constantly working with our partner’s development team, iterating product ideas, reporting bugs, and doing everything else to add value and stay front of their mind. Kudos to Max and the team!

What was the YC program like? What were the highlights?

Our YC experience was a bit atypical, because we had a remote program, raised our seed round halfway through, skipped the Demo Day, and had to leave before program conclusion due to a scheduling conflict, but it was still valuable.

YC gave us access to great minds in the Silicon Valley hall of fame. The founders of Airbnb (YC Winter ’09) gave our cohort’s kickoff speech, Marc Andreesen came to talk at one point, and a number of well esteemed YC alums shared with us insights in areas where they made their name — the Twitch CEO discussing consumer virality, the Segment CEO talking about harnessing the power of data, etc. — the exposure and learning were priceless. [Keyi note: Twitch (YC Winter ’07) is a leading gamer streaming platform valued at around $15B, and Segment (YC Spring ’11) is a SaaS company offering customer data management tools, recently sold to Twilio for $3.2B.]

The program is structured tightly around YC’s philosophy of pursuing growth relentlessly. All the “technical” training for founders is packed into the first 2 weeks. Over the remaining 10, you focus on growing your business as fast as you can, sprinting through one milestone after another set out in YC’s product launch roadmap, until you finally reach the Demo Day. By then, you are expected to have good traction and a polished fundraising pitch, and you debut in front of an expectant seed investor community on the edge of their seats to bet on the next YC unicorn.

You learn by running through one new challenge after another along the 3-month journey — hiring the right team, handling conflicts, etc. — and by leveraging YC’s rich reservoir of startup advice. Whether from books, blogs, time with YC mentors, or partner office hours, the advice invariably becomes a lot more relevant in the context of real-world problems you are fighting. YC is highly opinionated and not shy about instilling their beliefs in its cohorts, such as “Build Things That Don’t Scale” [Keyi note: a quote from YC founder Paul Graham that means pouring resources into iterating initial products to gain crucial knowledge about the market and customers]. We generally find their framework insightful and effective, but it is also geared towards early stages in the startup lifecycle. Scaling sustainably and developing a 10-year vision are not their focus.

[Keyi note: for those interested, Alan’s co-founder Val has a post on YC vs. Techstars here.]

You guys consummated several successful fundraisings last year, including a $2.1MM round led by NFX with participation from Y Combinator, Matchstick Ventures, Scribble Ventures, Mike Vernal of Sequoia and Harry Stebbings’s 20VC. Anything learnt?

One thing that really helped us was starting to build relationships with prospective investors very, very early on and being relentless. Max has been talking to some of our current investors for years, long before Warmly,. He had pitched one of them seven times on different ideas and got rejected seven times before they finally funded us.

We are also religious about updating our network frequently: since our early Techstars days, we have been sending weekly (now bi-weekly) business updates to an expanding group of mentors / advisors, current and prospective investors, and basically anyone who has supported or is willing to support us as we grow. The update would recap our progress and learnings for that week, actionable asks for help, and gratitude for those who helped. It has proved a fantastic way to not only let prospective investors get to know us but also nurture and leverage our broader network. We often receive dozens of responses to our calls for help, and without such support, we would not be where we are. [Keyi note: Alan’s co-founder Max wrote an in-depth piece on the power of the weekly mailing list.]

For a seed-stage VC pitch, the top two selling points are traction and team credibility based on our experience. Head off the conversation by showing real momentum with users, and your investors’ ears would perk up. Then you can delve into the big problem you are tackling, the market opportunity, etc. It is also crucial to highlight why you are the right people to pursue this opportunity.

What do you personally focus on as VP of Engineering? What has been the greatest challenge for you in this role?

Up until recently, I did not yet manage a big team of engineers as VPs of Engineering typically do. I sometimes work alongside our engineers (less so as we grow), but more importantly, I need to constantly think about gaps in our technical capabilities and operations and how to address them. For example, how do we capture job changes as close to real-time as possible? This is our bread and butter, and we must both stay on top of the data industry’s state-of-the-art tools and have our own secret sauce. I make sure we learn from the best industry experts, including some who used to run our largest competitors. For example, Derek Schoettle (ex-CEO of ZoomInfo), Allison Pickens (ex-COO of Gainsight), and Alex MacCaw (Chairman & Founder of Clearbit) are our angel investors and offer us incredible advice from his experience.

For me personally, the greatest challenge is not anything technical but rather finding the highest-leverage way to impact our business. Counterintuitively, what adds the most value often takes the least time and is more often about people than about things. Making incredible hires, empowering and motivating them, building a win-win partnership with our competitors rather than dodging them — such things create far more impact than spending nights and weekends producing “perfect code”. A lot of that code would be thrown out anyway as we iterate through ideas.

The size of our engineering team has grown a lot in recent months, which means my role is rapidly transitioning into a managerial one. It is a steep learning curve to climb but an exciting one too. We have ambitions of building a world class engineering culture at Warmly. So the whole engineering team actively meets with experienced CTOs, from recent YC founders to engineering leaders who have taken their companies through IPO. The idea here is that every engineer at Warmly, will be a great CTO of their own startup one day and can have this wisdom to draw upon. But it also enables us to see further than our experiences would allow us by standing on the shoulder of giants, as we build the right engineering culture together.

Two books I recently read, Extreme Ownership (Recommended by one of our own, Casey Dyer, an experienced engineering leader) and The Score Takes Care of Itself (recommended by a friend and fellow YC founder Paul Dornier), gave me good food for thought on leadership. The teachings resonate the most when you have context to apply them in.

You once mentioned the very different personalities of yourself and each of your co-founders. When starting from different positions, how do you achieve consensus on key decisions?

We try to exchange thoughts in writing as much as we can and only use live discussions to resolve any sticky points and make final decisions. We have a shared document where any of us can raise issues, propose solutions and explain ourselves. Everyone else would then document whether he/she agrees or has alternative ideas and why. With asynchronous thinking, each person gets enough time to process the issue, understand others’ positions, and put his/her best thoughts forward. This makes our weekly co-founder meetings focused and productive, and consensus a lot easier to reach.

Was there one experience or moment that really solidified trust and glued the four of you together?

Our time at Techstars was a beautiful bonding experience. We lived under the same roof and spent almost every waking hour of those three months together. Outside work, we shopped groceries together, cooked together, and took turns organizing weekend bonding activities such as group painting sessions and martial art practices.

As a daily ritual, Carina insisted that each of us share a personal story after dinner. It might be about a past relationship, something memorable from childhood, or even a lingering regret. Out of it came so many moments of voluntary vulnerability, nonjudgmental support and profound connections. Each of us has cried in front of the group during those sessions. We are really pushing the envelope to become not just co-founders, but also best friends.

Personal Journey

What was your path of self-discovery towards entrepreneurship like?

I have craved creating something of my own since I was a kid. In middle school, I read my first book on entrepreneurship — Delivering Happiness — the story about the trailblazing online shoe store Zappos, told by its co-founder Tony Hsieh. Its authentic “customer centric” philosophy left quite an impression on me. To ensure happy customers, Zappos started with happy employees. They pioneered a number of out-of-the-box work policies, such as offering all new hires $2,000 to quit after training in order to weed out anyone not passionate about the job and just here for the paychecks. They also innovated in every aspect of their business to make online shoe purchases a seamless experience — back when ecommerce was in its cradle and Amazon was still mostly selling books. Their happy customers then became a growing army of Zappos “sales reps”, and they barely needed to spend on marketing. This book was a true inspiration, revealing to me how a well-run business can be a powerful source of positivity and not just a money-making machine.

I kept the entrepreneurship idea back of my mind through high school and college, where the prevailing mindset was to get good grades and then good jobs along a few well-defined career tracks, such as finance and consulting. I remember discussing career choices with a mentor in my senior year of college. He himself has a one-of-a-kind background: once an economist at the Fed and on Wall Street, a lawyer at a prestigous firm, and a director at the Treasury Department, he is now a second-time startup co-founder and angel investor. He cautioned me that schools tend to shape students into familiar “molds”, which should never define my opportunity set. He encouraged me to stay open to nonlinear career paths, changing directions, and roads less traveled. I became a credit derivatives trader right out of college, but I kept his words in mind.

Having spent two years on the trading floor, I became convinced that professional service isn’t for me. I decided to bring the entrepreneurial voice from the edge of my mind to center stage, but before making the plunge, I needed to learn how startups are run from the inside. So I joined one called x.ai and learnt a ton there over the next two years. I also taught myself software engineering when I realized it would be a valuable skill for what I wanted to do.

In early 2019, I got a call from my childhood friend David. He acquired a Vietnamese restaurant in Dallas called Urban Caphe and asked if I would run it with him. And that was not his end game — David saw potential in a Zillow-like tech-enabled platform for restaurant buyers and sellers, and he wanted to use Urban Caphe as a guinea pig. I was sold, and within a few weeks, I transplanted myself from New York to Dallas and became a restauranteur.

The “Zillow for restaurants” idea did not ultimately take off, as we realized it would be difficult to recoup investments needed to build out the platform given the market size and monetization challenges. Neither did Urban Caphe work out unfortunately, but the learning experience was irreplaceable. In many ways, a restaurant resembles a startup: you need an attractive front end — the interior décor, the waiting staff, the menu etc. — to interact with customers, while the back end — the kitchen — is a constant tornado of chaos and holds key to the quality of your products and efficiency of your operations.

For a 2-week period that summer, our AC was broken. Can you imagine going to a pho restaurant on a humid 100-degree day without air conditioning? Neither could our customers! We were desperate to get the AC fixed, but the “market” for commercial AC contractors was like a jungle. We got quotes ranging anywhere from $10,000 to $50,000, which would be more than everything we had in the bank. Eventually, a friend of friend called in a favor and got us the “don” of local commercial AC mechanicians, who took care of everything for — 50 bucks. You heard right, someone else just tried to charge us 1,000 times that for the same job! After this incident, we thought about pivoting the tech platform idea into a “Bloomberg for restaurant owners” that would aggregate market data such as vendor costs and bring greater transparency to this opaque world. We didn’t end up pursuing it as I mentioned earlier, but it was an interesting thought experiment.

In the fall of 2019, I left Urban Caphe to join On Deck where I would soon meet Max, and everything followed from there.

What was your experience like growing up and navigating careers as an Asian/Chinese American?

Fortunately, I never had an identity struggle growing up. My environment was friendly, I had many well-adjusted Asian American friends to inspire one another, and we never felt held back by our cultural backgrounds.

Things got trickier as I entered the workplace. The trading floor where I worked was predominantly white at the time, and while it could be disorienting for any fresh graduate with its industry lingos etc., it was doubly so for someone like me who was not native to the dominant “bro culture”. For one, it felt almost socially unacceptable to not take or fake an interest in golf, when everyone else around office was watching Jordan Spieth on one of their monitors during the PGA season. Also, my coworkers would often quote American movies from like the 80s that I, unlike most white kids, did not grow up watching. As these references generally mean little to someone without the context, my coworkers would see the blank look on my face and joke about assigning “homework” for me. I knew they meant no harm, but I also became aware that our cultural differences made relating harder, especially in an environment that lacks diversity in background.

Things got notably better when I moved into tech, where diversity in background is keenly sought after, and Irish dancing and Indian food can be equally celebrated as football. In my experience, “purple cows” stand out in the tech industry rather than get punished or painted black and white.

What is one cultural heritage you are most proud of (it can be any object, tradition, idea, etc.)?

I have been a Wushu zealot since the age of 5. I was fascinated and determined to learn after watching Wushu movies like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. My family moved six times when I was a kid, and I insisted on finding a Wushu school nearby at every new home. The only time I could not, I managed to continue training out of a Wushu master’s home basement for three years.

Wushu is so closely tied to the Chinese culture, that you need to understand some of the language to appreciate its teachings. For example, a lot of moves have poetic and graphic Chinese names, such as 白鹤亮翅 (bai he liang chi) — white crane spreads its wings, and 野马分鬃 (ye ma fen zong) — parting the wild horse’s mane. And Wushu emphasizes 精神 “jing shen” a lot, which means some combination of spirit, grit, mindfulness, and concentration that is impossible to convey with one English word.

The years of Wushu practice instilled in me key values such as discipline, respect for the master, and trust in persistent hard work. I would be a very different person without this defining part of my life.

Keyi (Author): If you enjoyed this story, check out my other interviews in the Entrepreneurship of Life series (catalog with links at the end) and subscribe (for free) to get new stories delivered to your inbox. You can also find me on Twitter and LinkedIn.